It’s the 40th Anniversary of TWU’s 1980 City-Wide Strike

It was April Fools Day 1980, but the TWU Local 100 membership was not joking.

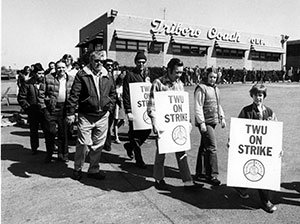

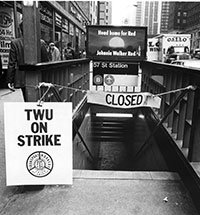

Thousands of New York City transit workers hit the picket lines on Tuesday morning, April 1, 1980, in the first City-wide transit strike in 15 years. The strike would last 11 tumultuous days.

New York City Mayor Ed Koch, who did more harm than good during the strike, lamented to the press: “The unthinkable has happened and now we have to figure out how to live with the unthinkable and we will.”

The man at the center of this watershed moment in TWU’s history was John Edward Lawe, a rugged Irish immigrant who had labored in a road repair crew and in Ireland’s peat bogs before arriving in America in 1949 at the age of 30.

Lawe, one of ten children to Luke and Kate Lawe from Strokestown, County Roscommon, Ireland, worked as an elevator operator in a Manhattan high-rise for one year before finding work as a Bus Cleaner for the old Fifth Avenue Coach Co. at the 132nd Street depot.

He became active in the union as a Shop Steward. During the 29-day bus strike in 1953, he served as a picket captain for maintenance. Later that year, Lawe switched to transportation and quickly rose up the union ladder. He was elected Transportation Section Chair in 1955 and then Chair for all of Fifth Ave. Coach Transportation. After the historic 1962 bus strike that led to the creation of MABSTOA, Lawe was elected Division 1 Recording Secretary immediately, and then Division 1 Chair in 1964.

Lawe served on the negotiating committee during the union’s first citywide transit strike in 1966. In 1968, he was elected Division 1 Vice President. Then in 1977, Lawe succeeded Ellis Van Riper as President of Local 100.

The decade of the 70’s was a turbulent financial period for New York City, which in 1975 teetered on the edge of bankruptcy. Who from that generation can forget the famous October 30, 1975 front page of the New York Daily News that blared “Ford to City: Drop Dead.” President Ford, the day before, had vowed to veto any Congressional bailout for the City.

It was also a period of relentless inflation. Workers were hard pressed to keep up with rising costs of food, gasoline and housing. Raises for city and state workers could not keep up.

After New Year’s Day, Jan. 1, 1980, the MTA began planting stories in the press claiming it faced an enormous operating deficit and that it could not afford increases for the workers. It was not a promising start to negotiations.

Lawe, who had won a hotly contested three-way election for Local 100 President in 1979, was having none of it. On Jan. 6, 1980, Lawe told the press: “If management does not bargain in good faith and give us what we are entitled to, we will give them the strike that they are looking for.”

The weeks rolled by quickly with no progress in negotiations. The MTA had presented the union with 41 takeaway proposals, including a demand that Bus Operators and Train Operators clean their own vehicles at the end of a run.

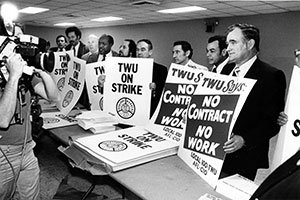

The MTA was playing with fire with Lawe, whom the press referred to in a kinder moment as “mercurial.” Midday on March 31, 1980 just hours before the “No Contract, No Work” deadline set by the union, the MTA finally made a wage offer.

It was too little, too late. After debating options until 2:00am, the Board and Lawe rejected the MTA’s offer and the strike was on.

For 11 days, that included Good Friday and Easter, TWU members manned the picket lines, vowing to stay out as long as it would take.

Finally, a public fact finding board recommended a 23 percent increase over two years, that included a 9 percent increase on April 1, 1980; an 8 percent increase on April 1, 1981 and a projected COLA of 6 percent on Oct, 1, 1981.

The Executive Board, however, remained deadlocked (22-22) on whether to accept the offer or continue the strike.

Lawe stepped in to break the deadlock. He decided, without objection from the Board, to send the proposal out to the membership for a vote. The strike was over. The membership vote was 16,718 to 5,477 as tallied by the American Arbitration Association.

But the fallout of the strike was just beginning. The courts came down hard on the union, fining all strikers two days pay for each day on strike under the onerous Taylor Law. The union was fined $1 million, a stunning sum for 1980, and as well, dues checkoff was lost for a period of time.

The strike caused an irreparable rift between the union, Mayor Koch and many of the City’s leading political leaders. City Council President Carol Bellamy angrily told Lawe that “I’ll piss on your grave” in a chance meeting after the strike. Lawe would tell the story with a chuckle, but the damage was obvious.

Photos from the top,Mayor Koch performs for the press at the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge, a young John Lawe’s employee head shot, members picketing at Triboro Coach in Queens Lawe greeting members on the picket line, Local 100 officers showing the media that the union is ready to strike; , and John Lawe with then MTA Chairman Richard Ravitch.